|

||||||||||||

History of The Church of St. Mary, Lydiard Tregoze, Swindon, WiltshireAlthough we have not been in contact with D. Attwood, the writer of the guide, we have been told we may reproduce it here and are very grateful to have that opportunity. The printed guide is available inside the church, with additional sketches by J. Hellewell. Lydiard Tregoz A Guide to the Church and its Monuments Text: D. Attwood

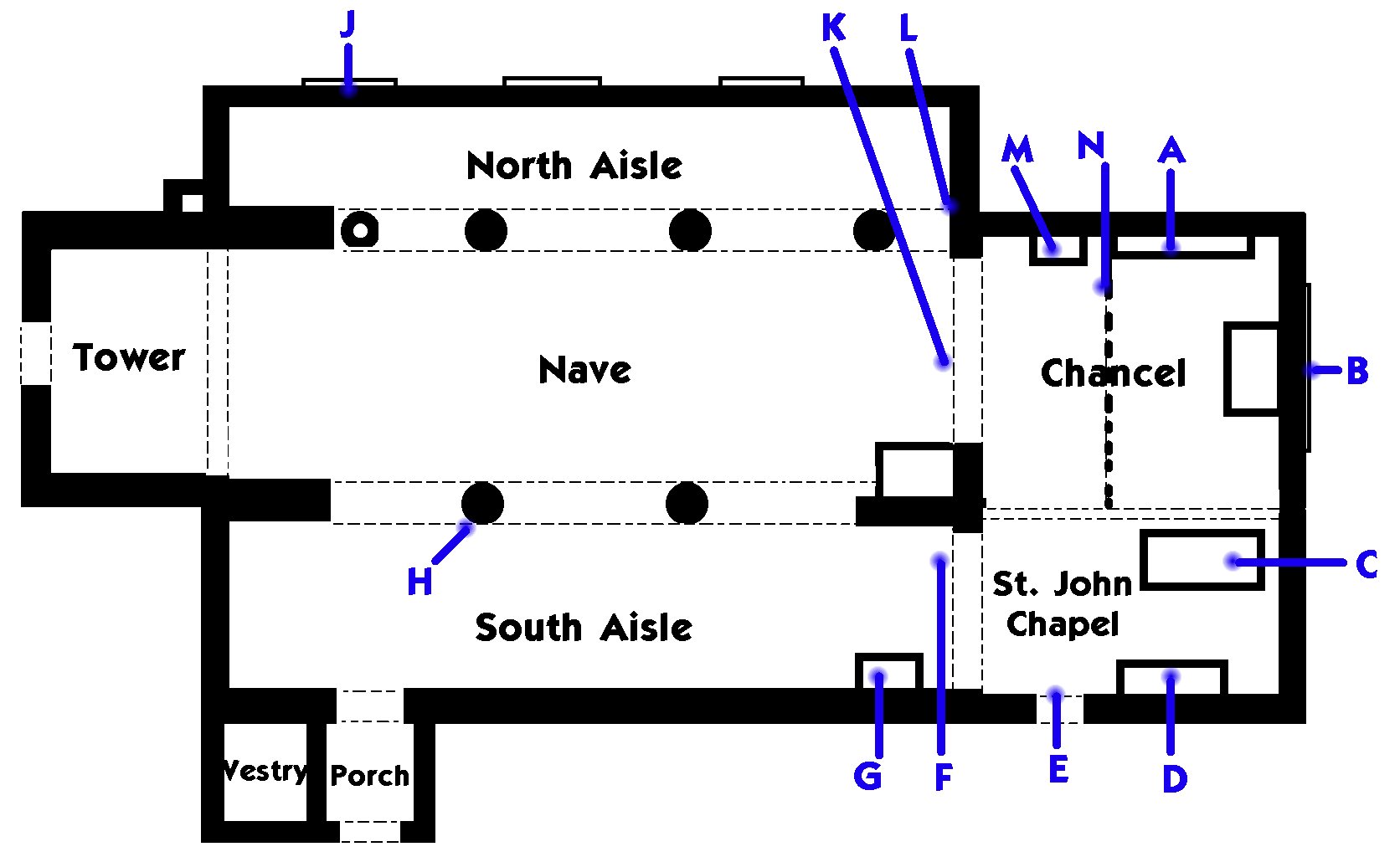

Floor plan of St. Mary's (not to scale) St. Mary's, Lydiard Tregoz, is just on the western edge of Swindon, in Lydiard Park. Coming on the M4, it is best to leave at junction 16. The key to the church can be obtained normally from Lydiard House, by the church, or from the vicar - tel. 870244 An Introduction As you step into the little parish church of St. Mary's, Lydiard Tregoze, it seems as if you step back hundreds of years into the past. The church owes its antiquities to two main factors - that the small hamlet nearby disappeared hundreds of years ago, and to the accompanying fact that the St. John family of Lydiard Mansion treated the church as a family chapel, taking care of it over the years and leaving their mark in the shape of the extraordinary monuments. Several of these monuments are outstanding on their own - the painted triptych of 1615, the St. John tomb of 1634, and the golden cavalier of 1645. These have been claimed by the authorities as "nearly if not quite unique" [1] (the triptych), "one of the most original and exciting monuments in Britain" [2] (the cavalier) and "among the finest effigies in England" [3] (the St. John tomb). Add the wall paintings - there are several paintings of Christ and the saints which are very unusual surviving examples - and the lovely atmosphere on which so many visitors comment, and you are in a church which is something special even in the vast range and history of English parish churches. [1] Sir Anthony Wagner (Chalinceaux King of Arms) [2] Christopher Hussey [3] Mrs K. Esdaile In spite of being so far from the centre of population, the church has continuously been used for worship, and still is every Sunday. The worshippers come from the farming community locally, including families with old connections who return each week to worship, from the new developments at Freshbrook, Grange Park and Toothill, and elsewhere. Together they have helped preserve and repair the building; so that in turn the monuments and paintings may be conserved. In doing this they are helped by those with particular interest in the artistic and historical aspects, who have formed 'The Friends of Lydiard Tregoz'. The Friends meet regularly to further research and knowledge about the church, the Mansion, the family and the monuments. Another group has undertaken the appeal for money to save the monuments and paintings. The appeal numbers among its patrons Lord Clark, Sir Hugh Casson, Sir John Betjeman and Miss Elspeth Huxley. This guide is an attempt to answer some of the most frequent questions that visitors ask about the church. How old is the church? Part of the church (the nave, and part of the left-hand (north) aisle, and the font) dates back to the thirteenth century; though there was a church here before then. But it was during the fifteenth century that the church was rebuilt, with a new roof, the tower, the south aisle, and the chancel and chapel. Many of the wall paintings were done at this time. The last major changes made to the church were made in the remodelling of the east end of the church. The stained glass east window was installed, and the chapel ceiling painted, with the wall between the chapel and the chancel replaced by the marbled pillars. What about the pews - are they old? Pews were first installed in the seventeenth century, and as they now stand they were completed by the Victorians when the main body of the pews was installed down the centre of the church. One of the first pews was the family pew with its high carved sides. The pulpit used to be under a pillar in the nave, looking across the church to the family pew. (This arrangement displayed in the model on show in the Mansion, which was made in about 1841.) The Wall paintings Many of the wall paintings date from the years 1400 - 1450 when the church was rebuilt. They were uncovered in 1901 and are in need of thorough investigation and conservation. However there is plenty to be seen and a good idea is given of how the church appeared when it was first painted. Where are the wall paintings and what to they depict? The most immediately striking painting is the Cross over the Chancel arch. On either side of the cross are the heads of four people. The Black Letter texts underneath these were painted after the Reformation. There are several paintings on the left hand side of the nave, starting from the tower. First there is clearly visible a soldier who forms part of the Martyrdom of St. Thomas a Becket. Next there is St. Christopher; there is a figure holding a lantern, a central spire, three trees, and the roofs of the houses are very clear. Then there are further fragments; those nearest the chancel are now covered by text. In the left hand aisle there are paintings but they cannot be identified until further work is done. Perhaps the most attractive of the paintings is a little one on a pillar of the risen Christ; you can see it by going into the right-hand aisle and looking at the nave pillar from beside the organ. This is a very colourful figure and would benefit from expert cleaning. Above this figure there is a picture of St. Michael weighing souls, with the Virgin Mary interceding. The banded figure is St. Michael. Looking towards the chapel there is evidence of more painting - which is a decorative pattern, and possibly another figure. One of the few distinctive paintings in the church is in the south porch. Very few porches are painted, and this one has a representation of the Head of Christ in a floral pattern on the inner wall above the outside door. When this is cleaned it will come up very clearly, and it will then be another of the striking features which make this little church so remarkable. These paintings will probably not earn a place for their artistic value, which was not why they were originally done. They were painted to stimulate devotion, and to teach the congregation. Even in their present state they give us a real insight into the world of five and six hundred years ago. Those were the years which gave us so many fine churches; but owing to the reforming zeal of the Puritans and Victorians concern for cleanliness and smartness, not much is left to us of their original paintings. A leading expert [Clive Rouse] writes about them "in some places large areas still remain to be uncovered and might reveal the most interesting subject matter ... Several subjects are most unusual in their content ie the half figure of Christ in an unusual setting in the South porch, and a previously unidentified painting in the South aisle. The treatment of the area above the chancel arch with the half figures surrounding the great rood or cross is another example virtually unique in my experience". Why is the coat of arms so prominent? This is the royal coat of arms of the Stuarts, ie between 1603-1688. It has not always been placed where it now is, on the chancel screen. About 100 years ago it was on the wall above the chancel arch, where the silhouette cross is now very clear. The royal coat of arms had to be displayed in churches in the time of Henry VIII, so all churches had them; this is an unusually fine set. In 1901 various changes were made in the church; the central part of the screen was replaced to bear the coat of arms, and at the same time the wall paintings were rediscovered. The Monuments Looking at the wall paintings, you are looking at the art and ideas of over five hundred years ago. When you step through the screen into the chancel and the St. John Chapel, you step forward two hundred years, for between the years 1615 and 1645 this part of the church was transformed, largely by the enthusiasm of one man, Sir John St. John (1585-1648). (As several members of the family at different times were called John St. John, we will refer to this man as the 1st baronet.) Which is the oldest monument? The painted effigy of a husband and wife kneeling side by side is the first of the monuments to be put in the church. It commemorates Nicholas and Elizabeth St. John, the 1st baronet's grandparents, and was put up by their son, Sir John St. John in 1592. The two kneel side by side under a richly painted canopy, covered with heraldry; it was repainted in 1886. The coat of arms above the monument is that of Walter St. John, the 1st baronet's elder brother, who drowned in 1597. The Nicholas monument, which seems modest by comparison with others, attracts many for its colour and simplicity. Was it this monument which inspired the young baronet? Clearly he inherited great pride in his family, although his father died when he was only nine, and he took great pleasure in the arts. One of his uncles was Richard St. George, who was Clarenceaux King of Arms and did some heraldic and genealogical work for the triptych. The 1st baronet was a wealthy man and he shared the seventeenth century obsession with human mortality. Over a period of thirty years he commissioned three remarkably different monuments - the triptych family portrait, his own tomb (the St. John monument), and the Golden Cavalier in remembrance of his forth son, Edward. Whom does the triptych portray? The triptych is the 1st baronet's memorial to his parents, and its central display is a family portrait of them and their children. These include the baronet himself and his wife; six daughters. The front four panels are covered with elaborate family trees; when the two outermost panels are opened more detailed genealogy and heraldry is shown. All this was added between 1683 and 1718. When the two inner panels are opened the central display is revealed. There is extravagant use of perspective, to portray the children gathered around their parents kneeling on the tomb. There is no doubt that it is the 1st baronet, and not his parents, who dominate the composition; his face and that of his father stand out whereas the ladies' faces, and all the hands, have a much flatter appearance. The St. John Tomb The 1st baronet did not leave it to his own sons to erect a monument to him, but commissioned it himself. It was erected in 1634 before he was fifty, and he still had another fourteen years to live. In it he commemorates his family - his first and second wives, and their thirteen children, all by his first wife. What is known of the members of the family? The baronet himself dominates the monument, and we learn a lot about him from this accurate effigy, from the triptych painting, and the two portraits in the house. These and the evidence of his work in the chapel and chancel give us great insight into his character. It is no surprise to learn that he purchased his baronetcy from James I for £1,095 at the earliest opportunity! His first wife, Anne, lies holding her thirteenth child - she died of exhaustion when this boy was two months old. His second wife Margaret was a widow and had already been effigied with her husband, Sir Richard Grobham, at Great Wishford near Salisbury. So during her lifetime she could see her sculpture lying on two tombs! Of the children, three boys and a girl died in childhood before the monument was built, and they are sculptured in relief on the north (altar) side of the monument on the plinth. This left six sons and three daughters. The eldest son Oliver married, but died before his father. His son John inherited as 2nd baronet at the age of twelve, but died as a young man of twenty. The next three sons all fought on the Royalist side during the Civil War, and all gave their lives for the cause. John died at Newark, and William at Cirencester. The fourth son Edward was wounded at Newbury and died nearly six months later. He must have been his father's favourite, for he is the Golden Cavalier. The two younger sons both fought for the Parliamentary armies; although not in the same battles in which their elder brothers died. Walter became 3rd baronet after the death of his young nephew, and lived until 1708. Henry the youngest child lived until 1679. Anne, the eldest of the daughters, married at eighteen, and again after the death of her first husband. Barbara also married but died in her twenties. Lucy married Richard Howe of Great Wishford, a relative of her stepmother. By the time the baronet died in 1648 at the age of sixty-three, only four of his thirteen children were still alive. Is the St. John Monument of real artistic value? There is no doubt that these effigies rank among the finest of their kind anywhere in the country. It is in the Italian style, and may have been the work of Nicholas Stone, the leading sculptor of his day. It is made of alabaster, with chalk and black limestone. It was almost certainly made in London and transported to Lydiard, where damage in transit was carefully repaired and the whole assembled. Of its quality, the best that can be said is - look at it. Look at the lifelike carving of the hands and faces of the baronet and his two wives, or at the eight children kneeling at either end. Look carefully at the clothing - the lacework is different on each of the sixteen members of the family. Look up at the heraldic symbols and crests of the canopy and at the four virtues, one at each corner. These are charity (with children), hope (with an anchor), immortality (holding a wreath) and faith (holding a book). The whole monument is a marvellous unity in style and quality. Who erected the monument over the chapel door? This monument was placed here at the time that the 1st baronet was remodelling the East end of the church, putting up the painted ceiling and marbled columns. The battlements of the south wall of the church, facing the house, were built at this time, and the date 1633 is placed over the outside of the chapel door. But it was not the baronet who put up this monument, which is to his eldest sister Katherine. The inscription in Latin tells us that it was placed by her husband Sir Giles Mompesson in her memory. Sir Giles Mompesson has an unhappy place in English history. Through the St. John family he was related to James I's favourite the Duke of Buckingham, and he was involved in a scheme to licence inns and ale-houses. Through administering this scheme, and the feed and fines it was designed to produce, he obtained considerable income. He also became involved in a similar scheme to do with gold and silver thread. The cruel and harsh way in which the licensing was administered gave rise to many complaints, and when Parliament met after a six years gap in 1621, Mompesson was tried and sentenced. He was severely sentenced, but fled the country during the trial, and thus escaped imprisonment and the loss of his knighthood. There cannot be many such villains commemorated as he is. The work is called by one writer "that first of English Conversation Pieces, the enchanting Mompesson monument". (English Church Monuments 1510-1840, by Mrs K.7nbsp;Esdaile.) More about the Golden Cavalier The cavalier commemorates Captain Edward St. John who died for the Royalist cause in the Civil War. There is nothing like it anywhere else - though there are one or two similar statues of the time, one in Broad Hinton Church not far away. Certainly no other statue is gilt like this one. Initially it was black, probably to simulate a black marble finish, and then it was coloured - as the canopy and page-boys remain to this day. The armour at least has been gilded for two hundred years, and possibly the whole statue. On the base of the statue there is a relief carving showing the Cavalier leading his troop of sixteen horses. The East Window This also dates from the time of the baronet. It portrays an olive tree in the centre, flanked by St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist. It is designed as a play on the Oliver St. John, and is in honour of the baronet's uncle Oliver 1st Viscount Grandison. It is the work of Abraham van Linge, the same artist who executed the remarkable painted glass window in Lydiard Mansion. The little boat to be seen under the tree also appears in the window in the Mansion. What else did the baronet put in the church? The baronet was responsible for three major monuments (to his parents, himself and to his son), for the East window, and for redesigning the East end of the church to provide a fitting setting for all of them. All this is known to be his work. It seems likely that he also gave his attention to the rest of the church. If this is so, then the painted and gilded screen was placed in the church by him. The pulpit and family pews are also Jacobean (James I, 1603-1628) so it is likely that the baronet also gave these to the church. Are there later monuments worth noticing? The only major monument placed in church after 1650 is the one of the 2nd Viscount St. John which stands in the South Chapel by the St. John monument. This is known as the Rysbrack monument, after the artist responsible for it. The church is full of memorial tablets and inscriptions. Parishioners and former rectors are remembered as well as members of the St. John family. What are the two large diamond-shaped frames hanging in the St. John chapel? These are funeral 'hatchments' or 'achievements' - painted of the full coat of arms of those who have died. These two are for the 2nd Viscount Bolingbroke (died 1787) and the 3rd Viscount Bolingbroke's first wife (died 1803). There are three other hatchments in the church which are earlier and smaller. Two in the south aisle (near the Nicholas monument) commemorate the baronet's first wife Anne (died 1628), and a brother-in-law of the baronet, Sir George Ayliffe (died 1643). One in the chancel wall near the triptych, above the window, is probably for Walter St. John, the elder brother of the baronet's father who died by drowning in 1597. The wrought-iron altar rail and the chancel ceiling The altar rail is elaborately covered with decoration and gilding. It is worth examining closely; it will appear in its true glory when it was been cleaned. In fact one of the falcons has already been cleaned and gives an inkling of how the whole should appear. The chancel ceiling with its painted sky, including sun and moon, has just been cleaned. During cleaning it was found that the ceiling was repainted in 1837, covering entirely the earlier painting. (The painters in 1837 left a little note just above the triptych.) These are among the details of the church's decoration that can easily be missed on a brief visit to the church. What else is there to look for in the church? This short guide has aimed to give some background information to help the visitor see more as he goes round the church. There is very much more to be noticed. Anyone interested in heraldry will obviously find a wealth of material of great interest, especially on the monuments, but in other places as well. But all will be interested to look for the falcon, the crest of the St. John family, which appears in several places. Many very attractive small pieces of very old (15th century) stained glass are easy to miss, and are well worth looking out for. One of the loveliest portrays the Virgin Mary (turn into the north aisle and it is directly in front of you). The three helmets date from 1580 to 1650. The oldest is in the nave, and the other two are in the St. John Chapel. The brackets in the St. John chapel were used for the hanging of banners and pennants which have not survived. The oil lamps that remain in the church were those used for lighting the church until 1953, when electric lighting was installed. Do take your time looking around, and enjoy the peace of a building which has been used for worship every week for hundreds of years. More details, and attractive colour illustrations, are contained in the official guide 'Lydiard Park and Church'. The Friends of Lydiard Tregoz always welcome new members; they meet every year and publish an annual report with articles about all aspects of the history of the family and the place. Anyone who would like to join the congregation in worship would be most welcome. Contact 1 Brandon Close, Grange Park, Swindon, Wilts. Tel: (01793) 870244. Services take place every Sunday at 9am, 10.30am and 6.30pm. Please note: the original guide uses the word 'Triptych' in its text, as did all literature we have read at the time. Recently we have noticed the correct description of 'Polyptych' is now being used. As the above is a copy of the leaflet, we have kept the original text.

HOME

|

Contact Us

|

Copyright

|

Donate

|

FAQs

|

Links

|

Location Index

|

Sponsors

|

Surname Search

|

Us

|

War Memorials

|

Wiltshire Collections

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||