|

|||

The Church of St. Peter & St. Paul, Broadwell, OxfordshireWhen we visited Broadwell a church member showed us around and invited us to take photographs of the pages of the history guide to use on this website. However our photographs are not very good so we decided to transcribe the text instead. Many thanks to the people responsible for collecting this information and producing the Guide and for allowing us to reproduce the information here.

Pages from the guide A spire in green fields between Burford and Lechlade The Shill and Broadshires Benefice Guide St. Peter & St. Paul. The purpose of this guide is to explain what you are looking at in and around the building and how it came to be built. Introduction. After the Romans left in AD 410 England reverted to paganism and the area from Burford to Lechlade became disputed territory between the Angles in Mercia, north of Burford, and the Saxons south of the Thames at Lechlade. The Saxons won the battle of Beorhford (a hill outside Burford) in AD 752 and the area became Saxon. Christianity was introduced from AD 600 by St. Birinus, a bishop from Rome, who set up a minister in the previously Roman Christian centre at Dorchester on Thames. A system of ministers, where a group of priests or monks lived and worshipped, and chapels-of-ease, outlying small churches to which a priest or monk travelled to preach, then spread out from Dorchester. Bampton became a minister with Broadwell and Langford as, initially, the chapels-of-ease. Then Broadwell and Langford became ministers with Holwell and Kelmscott becoming Broadwell's chapels-of-ease.

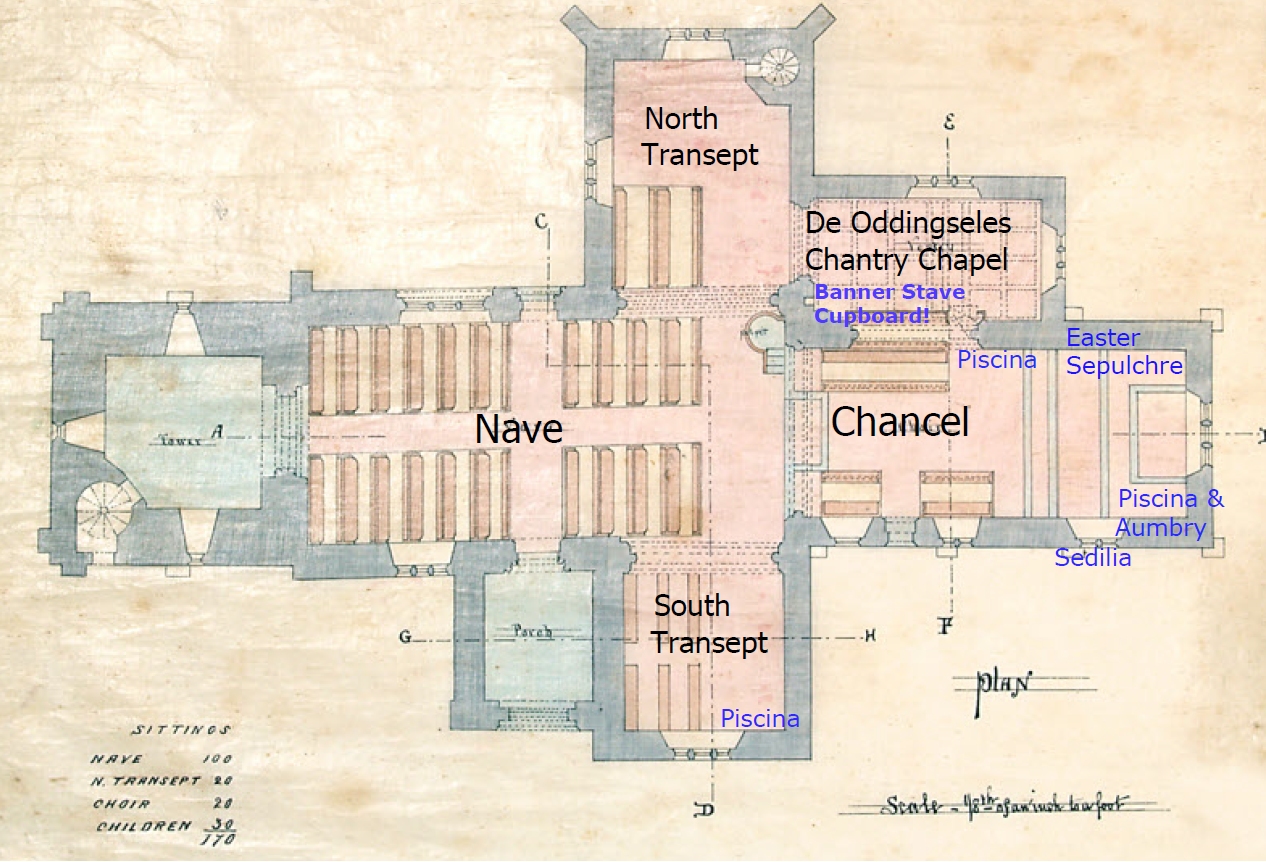

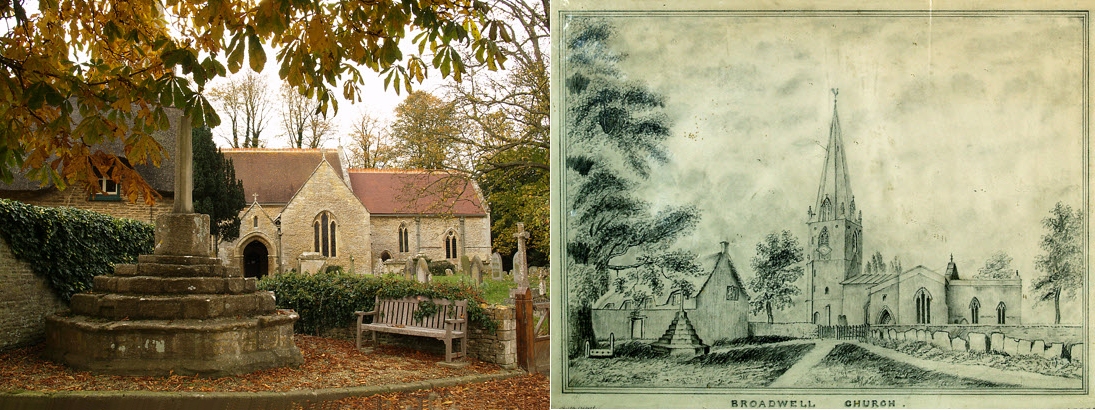

You are standing in a church with a large cruciform medieval design, with a north and south transept, which was probably built to this size at the outset in the 12th to 14th centuries - owing to the importance of Broadwell (or Bradwell) at that time. This Medieval Church Building. When built, the floor throughout the church would have been level, maybe earth or, probably, flagstones. The walls would have been plastered and painted. A wooden chancel screen would have separated the chancel from the nave. Priests or monks and, possibly, knights in white and red cross Crusader tunics would have prayed here. But now this large, steepled, medieval church stands in a small village of a few houses. Just beyond the eastern church wall is another village, Kencot. The Knights Templar. Broadwell is now extremely small but in the 12th century it was bigger than Burford with a population of approx 2,000. Did the Black Death kill the village in 1349 or was it the collapse of the Knights Templar, the benefactors to Broadwell? There is no evidence of the Black Death but the building of this church and its recorded history does coincide with the rise in power of the Knights Templar after the First Crusade in 1096, their official adoption by the Catholic Church in 1129, the gift of land in Broadwell parish at Filkins to them in 1185 and the building of the spire using their money in about 1260. By then the Knights Templar had built a vast international financial and military empire such that the monarchs of Europe were indebted to them. King Philip IV of France pressuresed Pope Clement V to declare the Knights Templar heretical and the Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, was burnt at the stake in Paris in 1314. A timescale perfectly in tune with the building of this large and magnificent church and, possibly, the decline of Broadwell village to smaller proportions. The church doesn't face east but north-east, 45 degrees, which accords with the Templar's practice of aligning churches with sunrise on the Patronal Saint's day, 29th June for the Saints Peter and Paul. Architectural Features to note.

The church has some interesting architectural and historical features; did you notice the fine dog-toothed,

Norman arch, left, by which you entered? That was probably the original external doorway as the

porch was added sometime later, maybe not until Victorian times.

The church has some interesting architectural and historical features; did you notice the fine dog-toothed,

Norman arch, left, by which you entered? That was probably the original external doorway as the

porch was added sometime later, maybe not until Victorian times.

Note the 12th century quatrefoil font, its nail-head frieze and the long carved face on the east side. It stands in front of a 12th century tower arch of fine roll-moulded form on shafts with scalloped capitals. In the tower itself there are traces of Saxon rubble brickwork indicating that this church ws probably built on the site of an earlier one. Saxons, the Conquest, the Normans and after. The Doomesday Book states that Broadwell manor belonged to Cristina, daughter of Edmund the Exile, brother of Edward the Confessor. She returned to England from Hungary in 1057, with her father, but was dispossessed of Broadwell soon after the Doomesday Book and died, probably before 1100. The manor was granted to a Norman knight, Ralph de Limesi, from north of Rouen, who also had lands in the Midlands. His male successor died in 1197 when Broadwell passed by marriage to the "de Oddingseles" family who are commemorated by the chantry chapel in the present church. We owe this fine church with its octagonal spire, circa 1260, to the stewardship of this family and the benefaction of the Knights Templar. Ralph's son, Alan de Limesi, gave considerable land at Filkins to the Knights Templar in 1185 or soon after when the London branch was established. At this time Broadwell was in the Lincoln diocese; records called Liber Antiquus at Lincoln record "Bradwell" as an independent parish, with two chapels-at-east at Kelmscott and Holwell, all before the Magna Carta in 1215. By then Broadwell (Bradwell) church had been built much as you see it today, and it remained in the Diocese of Lincoln from 1072 till 1542.

The de Oddingseles benefactors, Knights Templar financiers, Master craftsmen and others who built this church might be watching you from the Nave corbels, above, which support the roof. (However, these are restored corbels - do they faithfully portray the originals?)  From the Conquest until Henry VII's time this medieval church would have been monastic in nature especially

with the influence of the Knights Templar. The chancel probably had an altar table in the centre and a

Piscina, for washing the chalice, on the right hand side. The one, right, is a splendid 13th century

example but has been moved to the south transept. Simpler piscinae, as below, now remain in the chancel,

one a 19th century Pedestal type.

From the Conquest until Henry VII's time this medieval church would have been monastic in nature especially

with the influence of the Knights Templar. The chancel probably had an altar table in the centre and a

Piscina, for washing the chalice, on the right hand side. The one, right, is a splendid 13th century

example but has been moved to the south transept. Simpler piscinae, as below, now remain in the chancel,

one a 19th century Pedestal type.

This was a principal parish church for the area between Burford and Lechlade, an importance which resulted

from its initial chapelry status to the minister of Brampton during the birth of Christianity in the area,

followed by its own later minster status. This importance could mean that the chancel, with a flat

floor, would have been used for monastic type services. This would account for the numerous piscinae,

the window sedilia (left) and the hinges in the east wall, behind the altar, which may have been an aumbry

(dry cupboard), although there is also an aumbry by the pedestal piscina.

This was a principal parish church for the area between Burford and Lechlade, an importance which resulted

from its initial chapelry status to the minister of Brampton during the birth of Christianity in the area,

followed by its own later minster status. This importance could mean that the chancel, with a flat

floor, would have been used for monastic type services. This would account for the numerous piscinae,

the window sedilia (left) and the hinges in the east wall, behind the altar, which may have been an aumbry

(dry cupboard), although there is also an aumbry by the pedestal piscina.

The Window Seat (Sedilia) The sedilia would have been used by 12th to 16th century monks or priests to rest during long services. However, the Victorian Restorers had a passion for tiled floors; they raised and tiled the chancels and the altar areas everywhere they worked. This has made sedilia and other medieval features look ridiculously close to the floor.

Three Scalloped Panels?? Left of the altar - these three scalloped panels, 15th or 16th century judging by the design of the tops, are a mystery. They may have been an Easter Sepulchre for housing the sacrament during Holy Week. After Henry VIII to the Victorians. All monastic orders ceased under Henry VIII and churches supported by them often fell into disrepair because villages could not adequately maintain them. Broadwell appears to have fared better as the manor held rich farming estates. The next major reconstruction came with the Victorian Restorers and one, E. G. Bruton, worked on Broadwell in 1873. He stripped the medieval plaster and paintings off the walls and reroofed the nave, chancel and transepts with a steeper pitched roof - maybe owing to the harsher winters and greater snowfall which occurred between 1810 and 1899. However, the de Oddingseles chantry chapel retains its original flatter roof from its original construction for Hugh de Oddingseles who died in 1305.

It is E. G. Bruton's plan of the church from 1873 which is used above to identify items of interest. The Chantry Chapel, the de Oddingseles and a link to chivalry of a Knights Templar type.  The chapel houses the unique feature of this church, sometimes referred to as a "banner stave cupboard" in

which case it would have been used to store the staves used for Sunday processions. Such cupboards

are common in East Anglia, but not in this area, and are usually in the south west of the church or in the

tower.

The chapel houses the unique feature of this church, sometimes referred to as a "banner stave cupboard" in

which case it would have been used to store the staves used for Sunday processions. Such cupboards

are common in East Anglia, but not in this area, and are usually in the south west of the church or in the

tower.

The cupboard opening is only 16.5cms (6 1/2") wide leading to a recess 33cms (13") by 54 cms (21"). A.S.T. Fisher, who wrote a very comprehensive history of Broadwell, Kelmscott and Holwell, thought it likely that the de Oddingseles, as knight benefactors to the church would have wanted to store the lances, swords and shields of deceased knights in the church. The first and second Hugh de Oddingseles fought beside the Kings Henry III and Edward I of England between 1220 and 1305 and would have been buried here. As this recess is in their chapel, builty by them, one must accept that this is a very plausible explanation. However, I have found no record of them having been Knights Templar.

The 13th Century de Oddingseles chantry chapel was originally used to house the family tombs but these were

placed under the floor in the Victorian era.

The 13th Century de Oddingseles chantry chapel was originally used to house the family tombs but these were

placed under the floor in the Victorian era.

The chapel also boasts its original medieval roof, supported on heraldic corbels, left, and a fine stone wall tablet to John Hubbard 1668. The power and land holdings of the de Oddingseles declined due to Henry VII's law and further after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538 and the final disbanding of the English Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem, successors of the Knights Templar, in 1540 by Henry VII. The manor of Broadwell "passed" to Thomas Pope, Treasurer of the Court of Augmentation of the King's Revenue, the son of a yeoman farmer from Deddington. Again, after Henry VIII into the 17th Century and Onwards.  From Henry VIII's time until the Gothic Revival from 1830 to 1900, which featured such names as Pugin,

Gilbert-Scott and George Edmond Street, the history of Broadwell was more involved with farming, manor

houses, payments to the poor and many other rural matters which did not affect the church buildings.

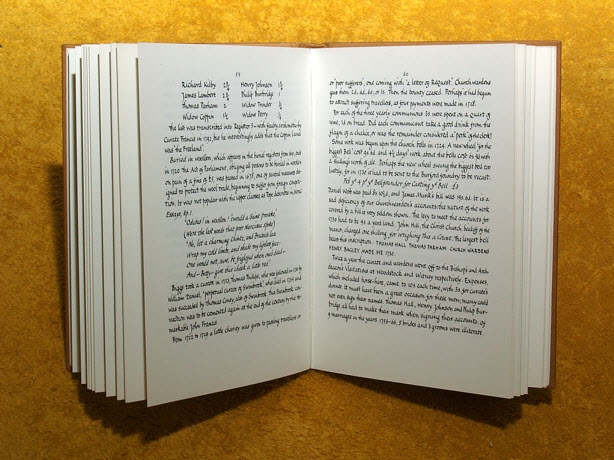

During the 1960s the Reverend A.S.F. Fisher, Vicar of Holwell, extensively researched the history of

this area and wrote three comprehensive books which he published privately in his own handwriting, see left.

From Henry VIII's time until the Gothic Revival from 1830 to 1900, which featured such names as Pugin,

Gilbert-Scott and George Edmond Street, the history of Broadwell was more involved with farming, manor

houses, payments to the poor and many other rural matters which did not affect the church buildings.

During the 1960s the Reverend A.S.F. Fisher, Vicar of Holwell, extensively researched the history of

this area and wrote three comprehensive books which he published privately in his own handwriting, see left.

From 1599 the local names which appear in parish records are Hampson, Thompson, Goodenough (still present today) and Cripps (from whom Sir Stafford was descended) and many others who came and went again. During this time nothing is recorded about the church buildings themselves but the 1800s were characterised by severe winters; the Thames froze in 1814 and fairs were held upon the ice. Records show that heavy snowfalls occurred from this time until 1899. Medieval church roofs had shallow pitches and were almost flat in some cases. Probably they had fallen into disrepair because it was during the period of the Gothic Revival that the Victorian restorers repaired churches, laid tiles in the chancels and nave and increased the pitch of all the roofs they repaired, as here in Broadwell Church. All followed the Gothic revival fashion.

In the tower, north transept and above the pulpit (shown left), there are examples of building modifications. It is evident that wooden galleries and rood screens existed in the church, probably from medieval times until the Victorian era. The plans which survive today drawn up by the Victorian restorers in 1873 show a definite rear gallery. The blocked door is a mystery but, maybe, a rood screen built to use the door shown left would probably have had a large platform top and been big enough for miracle plays to have been performed upon it for a mainly illiterate congregation.

Externally we can still appreciate aspects of the medieval village. The post and steps for broadcasting news survive although the stocks do not. The present church porch is a second version dating from 1873, the one in the drawing was a little earlier. Also the churchyard wall has been moved forward to the road and the village green no longer exists.

Left to right: the chancel window, the trefoil low level aperture in the tower and the south transept dial.  Externally, the church has windows from recognisable architectural periods, like the Decorated period

(1250-1350) chancel window above, but it also has idiosyncrasies like the low level trefoil window in the

tower and two sets of scratch dials (sundials) to indicate service times - no south

wall because the church does not face true east, the chancel is on a north axis.

Externally, the church has windows from recognisable architectural periods, like the Decorated period

(1250-1350) chancel window above, but it also has idiosyncrasies like the low level trefoil window in the

tower and two sets of scratch dials (sundials) to indicate service times - no south

wall because the church does not face true east, the chancel is on a north axis.

Along the road are the two gate pillars to the original Broadwell manor which was burnt down in about 1740. These pillars, the layout of the area and the magnificence of the church indicate clearly Broadwell's important place in our local history. Revision 11 July 2010 to add Knights Templar comment on page 3. Acknowledgement and thanks are due to June Goodenough and Jack Auger for on-site assistance. Sources of information have been AST Fisher's Histories, John Blair's Anglo-Saxon Odfordshire, Victoria County History and English Heritage. Photographed and produced by Derek Cotterill, 2007.

HOME

|

Contact Us

|

Copyright

|

Donate

|

FAQs

|

Links

|

Location Index

|

Sponsors

|

Surname Search

|

Us

|

War Memorials

|

Wiltshire Collections

|

|||

|

|